Keep reading about similar topics.

Research from Healthy Building Network (HBN) documents how vinyl building products, also known as PVC or polyvinylchloride plastic, are the number one driver of asbestos use in the US.

The vinyl/asbestos connection stems from the fact that PVC production is the largest single use for industrial chlorine, and chlorine production is the largest single consumer of asbestos in the US. [1] More than 70% of PVC is used in building and construction applications – pipes, flooring, window frames, siding, wall coverings and membrane roofing. [2] This makes the building and construction industry the single largest product sector consuming chlorine, bearing sizeable responsibility for the ongoing demand for asbestos. [3]

Despite the existence of asbestos (and mercury) free chlorine production methods, [4] the PVC industry has positioned itself at the vanguard of industry efforts to frustrate stronger asbestos regulation. According to Mike Belliveau, the Executive Director of the Environmental Health Strategy Center and a senior advisor to Safer Chemicals Healthy Families coalition, “The PVC market has spurred chemical industry lobbyists to urge the Trump Administration to exempt their use of deadly asbestos from future restrictions.” The last time the vinyl industry positioned themselves so publicly on the other side of common sense, they were defending the use of lead in children’s vinyl lunch boxes.

The health hazards of asbestos exposure, painful and deadly lung diseases including cancer, are clear. Green building professionals do not have to wait. Do your part to prevent asbestos-related diseases here and abroad. Don’t specify vinyl building products.

1. In the US more than half of chlorine is produced using asbestos, despite the availability of an alternative production method that does not require either asbestos or mercury.

2. http://www.vinylinfo.org/vinyl/uses

3. According to IHS Markit, “A majority of chlor-alkali capacity is built to supply feedstock for ethylene dichloride (EDC) production. EDC is then used to make vinyl chloride (VCM) and subsequently used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This chain, EDC to VCM to PVC, is normally called the vinyl chain. PVC demand correlates closely with construction spending, therefore, it can be concluded that chlorine consumption and production are driven by the construction industry. Hence, chlorine consumption growth depends on the growth of the global economy, since a country will spend more on construction if it has a healthy gross domestic product.” (IHS Markit. “Chemical Economics Handbook: Chlorine/Sodium Hydroxide (Chlor-Alkali),” December 2014. https://www.ihs.com/products/chlorine-sodium-chemical-economics-handbook.html)

4. For more information on asbestos-based and mercury-based chlorine production methods see: https://healthybuilding.net/news/2016/10/03/pvcs-asbestos-mercury-problems

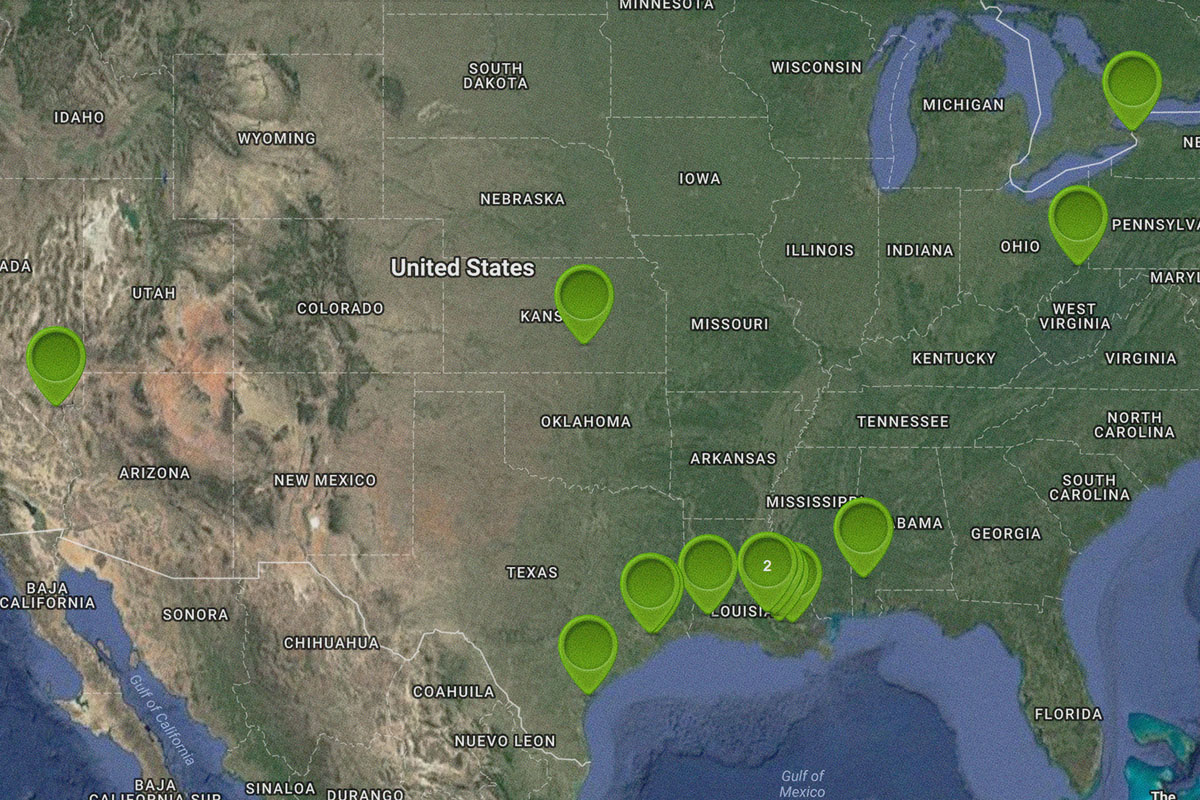

5. Fifteen chlor-alkali plants last reported to be using asbestos diaphragms include, in order of estimated chlorine capacity:

6. Carpentier, Steve. “Minaçu, a cidade que respira o amianto.” CartaCapital, May 21, 2013. http://www.cartacapital.com.br/sustentabilidade/minacu-a-cidade-que-respira-o-amianto-8717.html